How to Do Something: Redirecting Your Attention

Two of my favorite books on resisting the attention economy

I once came across an anecdote that suggested your interpretation of a book can change depending on the context in which you read it. For example, if you reread a book you will very likely notice something that you didn’t the first time. Or, you may find that you aren’t connecting with a specific book at a particular time in your life, but if you revisit it later, it will grab you with a force. Or you’ll find that what you have previously read largely influences your opinion of a similar book.

The latter is what happened to me with How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell.

Published in 2019, this book has received many accolades and was a New York Times bestseller. When Ezra Klein and Jia Tolentino, two of my favorite thinkers, both touted Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing as one of their favorite books, Ezra in particular saying it was “the best book on attention” he’s read1, I immediately moved it up in my mental TBR.

I set out thinking I would learn about the attention economy writ large but this book was so much more. It was a manifesto for the political resistance, a reclaiming of our human animality, an appreciation for nature, and a call for collective action.

When telling a family member about it, they asked if it was self-help. At the onset you would think that, but it very quickly evolves into something larger—Odell herself says it’s “an activist book disguised as a self-help book.”

At its core, her book argues for the necessity of “doing nothing” in an age where technology and social media are continuously more invasive. She defines the act of doing nothing not as stopping to do things completely, as the title might suggest, but rather as “refusing productivity and stopping to listen.”

I boiled this down in my mind to two iterations of “nothing”:

First, doing things that are not seen as “productive” in the capitalist sense, i.e. rest, maintenance, and caregiving. This can be anything from volunteering at the city’s rose garden to mothering your child.

Second, giving the brain time to reflect and think, without distraction. This can quite literally mean sitting there and doing nothing other than thinking or observing, or take a more active form like walking (by yourself with no technology), journaling, meditating, etc. The key is that it’s a form of solitude.

What I loved about How to Do Nothing is that it magically tied together all these seemingly disparate topics in my mind (nature, technology, community) into one cohesive, intersectional reality. Immediately upon starting it I felt seen and validated, like Odell was articulating so many of the thoughts swirling around my brain, including my inspiration behind “The Conscious Consumer.”

I also enjoyed how frequently Odell referenced works of art to demonstrate her points. As someone who doesn’t have a lot of encounters with art, I found this lens to be an incredibly eye-opening way in which to view things. And in all honesty, it made me reconsider the value of such art in our society—as a mechanism for changing minds and encouraging deep thinking. After all, isn’t that what writing is?

Reading this brought to mind another favorite book of mine, Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport. His is the first book I read on the attention economy and was an invaluable reference point for reflecting on how I want to construct my relationship with technology.

Newport spends much of his book discussing how, in a 30-day digital declutter, you can redirect your attention to things that better serve you and the life you want to live, and why this matters.

Nearly two years have passed since I read Digital Minimalism. In looking back on it now in comparison to Odell’s book, Newport writes with a much more individualistic approach. A productivity-hacking and efficiency-oriented mindset, if you will. While he doesn’t outrightly call it that or use those terms, if I expand the lens of his words outward to his personal brand and other works he’s published, it becomes more evident.

Newport’s book answers the question of, how do we set better boundaries with our technology? It brings a level of awareness to our attention insofar as we normally understand the attention economy in the context of the tech giants.

Odell’s book, on the other hand, blows up that scope entirely, redefining the bounds of our attention and what that might look like in a society that dares to orient itself by something other than a capitalist perspective. While individual action is necessary, she roots it in the grounds of collectivism.

I don’t intend this as a criticism of Digital Minimalism, by any means. I would still recommend that book to anyone looking for a tangible blueprint to change the way they approach their relationship to technology. And I would likely reread it. (In fact, upon flipping through my copy while writing this, I felt compelled to read it again.)

However, what I do intend is to look at both books with a discerning eye so you don’t take for granted what you are reading. If I expand the context of these hugely impactful books to the nature of who wrote them, I notice some things.

Jenny Odell is a 39-year-old woman of color and an artist who grew up and still resides in Silicon Valley. She taught Internet art and digital/physical design at Stanford.

Cal Newport is a 43-year-old white man and professor who was raised and still lives on the East Coast. He teaches computer science at Georgetown University.

As educators in the technology realm, both at prestigious universities, and spanning only 4 years apart in age, Odell and Newport have a lot in common. Their books were published just two months apart in 2019. Their born identity and inherent privilege, i.e. gender and ethnicity, however, differ greatly, as does the ethos of a computer scientist versus artist.

I call these differences out because I can’t help but wonder how their occupation and gender influenced their individualist versus collectivist approach. The computer science profession is arguably more “valuable” in the capitalist sense than the artist, so naturally it make sense to apply one's thought within the constraint of that system, perhaps without even realizing it. While the artist is likely more accustomed to thinking outside those constraints by the very definition of their role. This difference is further exaggerated by gender—where the role of caretaking and nurturing largely falls on women's shoulders in our society, it seems inevitable that care as a form of meaningful attention is brought up by the female author.

As Odell writes: “Our very idea of productivity is premised on the idea of producing something new, whereas we do not tend to see maintenance and care as productive in the same way.” She goes on to celebrate mothers as an obvious example of “work that sustains and maintains,” then extends it to caring for one’s community members and even nature and other animals.

To his credit, Newport calls out the gender influence, referencing feminist Virginia Woolf’s acknowledgment of solitude as “a form of liberation from the cognitive oppression”, much like Odell cites Audre Lorde’s definition of self-care as a form of activism. However, where Newport stops short, Odell picks up the reins: Newport puts the onus on each individual to improve their technology relationship, while Odell recognizes not everyone has the "margin" to think about where their attention goes and thus those of us who can afford any space and time to reflect on it must, in an attempt to help the greater good.

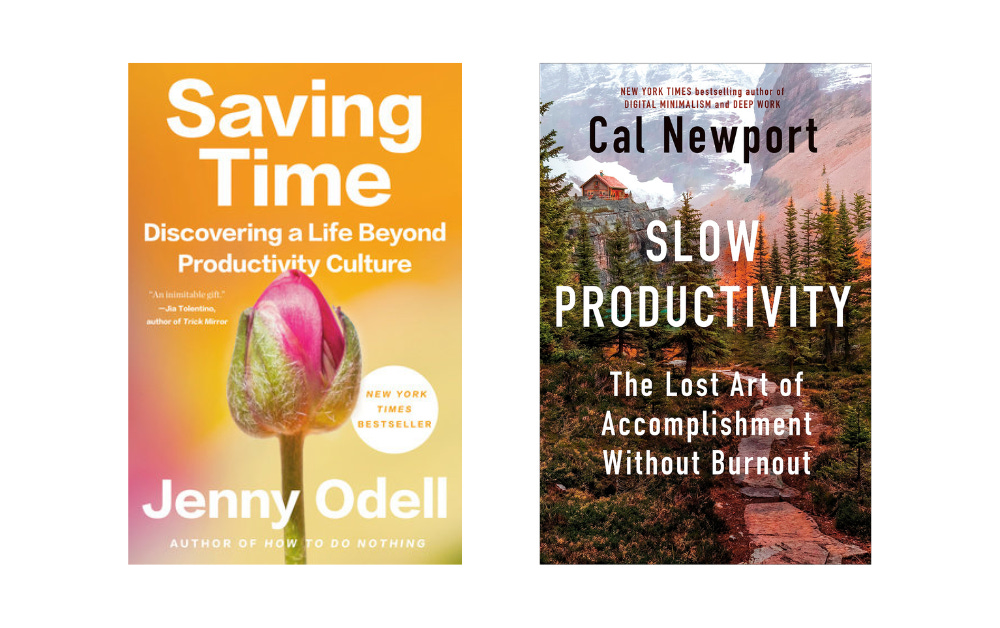

This difference in an individual versus collective outlook appears again in the follow-up books Newport and Odell published.

When I place these books side by side, again published mere months apart in early 2024, the contrast in their scope on an attention-related topic—time, in this case—is uncanny.

They both appear to seek to answer the question - how can I make better use of my time?2

They both use the word ‘productivity’ in their title - a marketing tactic, is my guess. Without knowing much about how nonfiction book titles are created, I’m certain that injecting the societal buzzword of “productivity” will instantly get more hands to pick the book up off the shelves.

However, the use of that time, i.e. the answer to the question they seek, has a different scope and application entirely. Odell extends the definition of time to go beyond productivity culture, redefining the cliche “time is money.” In other words, I expect it to answer, how can I make better use of my time in a world where producing monetary value doesn’t matter?

Newport applies the concept of saved time to achieving more and in a better way, i.e. the title suggests that by going slower we can avoid burnout. While it sounds great on paper, this keeps the concept of time within the societal constraint we have built. In other words, I expect his book to answer, how can I make better use of my time so I can be more successful?

I have not read either book, nor am I sure if I will. At the time of writing this essay, I am instantly more drawn to Odell’s because it alters the very question itself, but that could be a recency bias due to having just finished How to Do Nothing.3

Nevertheless, based on their titles and synopses alone, it appears that the collective mindset will permeate Saving Time and the individual mindset will permeate Slow Productivity, much like How to Do Nothing versus Digital Minimalism.

Each author’s lived experience and subsequent book withstanding, what I appreciate about both their voices is the shared emphasis on resisting the attention economy and the importance of solitude.

If Digital Minimalism is the guidebook on redefining your relationship with technology, then How to Do Nothing is a meditation on your relationship to humanity and nature sans technology.

It is clear that both Odell and Newport value redirecting attention away from all the sources that fight for it to something more intentional and substantial.

The question is where to redirect that attention—in service of your own conservation, or of society’s?

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/09/03/opinion/ezra-klein-podcast-jia-tolentino.html

One of humanity’s ultimate questions as an attempt to understand our place in the universe, that we will likely never stop answering 🙃

What gives me pause is thinking that, at face value, her second book looks quite similar to Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks, which I loved and perhaps would reread before turning to Odell’s thoughts on time.

I love the comparison here, Morganne – how interesting to see the different approaches these authors took, and how their backgrounds likely informed said approaches. The collectivist approach, though likely more difficult to achieve, seems like it would be the more long-lasting option. I think we talked about how I read some of How to Do Nothing but never finished. I think it might be time for me to pick it back up again!

Thanks for this piece, Morganne ! I especially like the undercurrent question about the place of art in our society.

In July I read a whole stack of fascinating papers compiled about the relationship between art and work. It turns out that during Middle Ages, the word "art" litteraly meant "work" (thus the ...artesans). I still ponder about that.